From the recently published book:

Manfred G. Schmidt, Via Augusta Baeticae. La vía Augusta de la Bética y sus inscripciones, Zaragoza 2021

Luxurius stands at a turning point of Roman history in Africa: The historical references in his epigrammata point to the very end of the Vandal kingdom and thus to the end of Roman culture, which with Luxurius loses its last poet on African soil.

The violent rise of king Geiserich is certainly the most famous phase of the hundred-year history of the Vandal Empire: He had laid its foundations in the Western Mediterranean by transferring his forces and the whole entourage in AD 428 from Spain to Africa; about ten years later he captured Carthage and in 455 confirmed his claim to power in the western hemisphere with a drumbeat: With the sacking of Rome by his barbarian hordes.

For mutual reasons, the military conflicts with Western and Eastern Rome then remained a constant companion to the formation and consolidation of the Vandal dominion. And the threat from the Berbers at the southern border as well as in the highlands did not calm the kings from Geiserich to Gelimer (AD 428-534) either. In addition, the former province of Africa proconsularis was shaken by internal turmoil of religious fundamentalists. The conflicts of the 5th and 6th centuries between Vandal Arians and Roman Catholics, the activities of the Donatists and the so-called circumcelliones (Augustinus) in Northern Africa have shaped a picture of the Vandal period that bears witness to a deep social insecurity of broad population strata in this rich and fertile country, which has always been considered the ‘granary of Rome’.

And yet there existed also a totally different world alongside: an independent culture had developed around the sparse ruling class of Vandals and their provincial Roman functionaries, and Roman living and culture was preserved and even developed in the upper circles of Carthage. Procopius of Caesarea (Maritima), a contemporary witness and close confidant of the Eastern Roman general Belisarius, retrospectively castigates the effeminacy of the Vandals, and thus gives us an insight into life and living in Africa Romana at that time:

Warm baths, sumptuous banquets and luxurious clothing, entertainment at theatre performances and horse races, hunting, music and drama determined their everyday lives; in magnificent villas they indulged in drinking and sexual debauchery (Procop., Bell. Vand. 2,6,6) – in Vandal Carthage one could obviously live quite well – just as in Martial’s Rome.

Procopius’s portrayal of the state of affairs at the Vandal court is almost confirmed by Luxurius’s contemporary poetry and the themes conveyed by his approximately 90 epigrams – however, the motivation to choose these subjects for his poems may have been different. Especially in the scoptic epigrams (satire verses) we see a clear match with the sociocritical remarks of Procopius. But we also witness the Roman way of life in the epideictic epigrams: objects such as amphitheatres, gardens, baths represent the space for the social life described in the scoptic poems. The image of a manifold city life full of amusement and debaucheries is ever-present – a dance on the volcano.

For our rather tedious question, which is devoted to the extent to which the poems of Luxurius can be set alongside genuinely inscribed texts, and should perhaps even be regarded as epigraphic evidence, we will draw on these epideictic epigrams. With their focus on real objects, they are from the outset very close to epigraphy. For an epigraphic text is, as we know, inconceivable without a monument. And of course also the two epitaphs (AL 345 and 354 R.), which have been preserved in Luxurius’s liber epigrammaton, show a clear reference to epigraphic tradition.

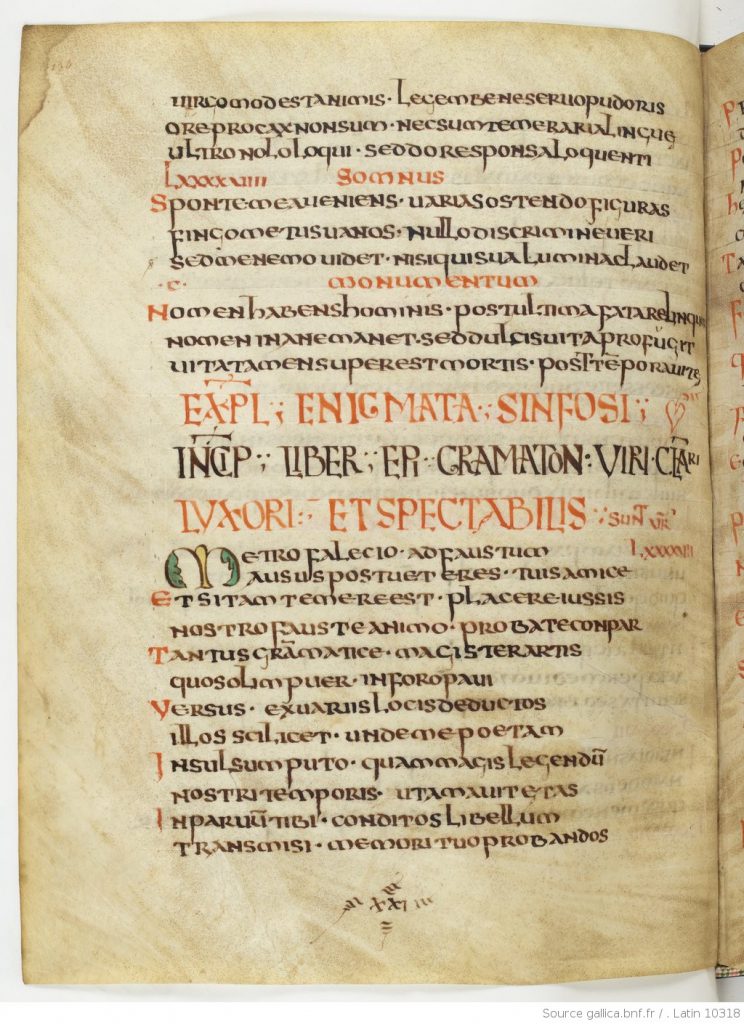

This late flourishing of Latin poetry, written by the still young poet under Hilderich (AD 523-530) and edited immediately after the last king Gelimer (AD 530-534) by a befriended grammarian named Faustus, is at the same time the chronologically last one in the anthology, which became known under the name ‘Anthologia Latina’. With the liber of Luxurius we also have a chronological reference point for the formation of the anthology as an edition of various small poems in the middle of the sixth century (Happ I 118f.), so that Shackleton-Bailey can summarize the question of chronology as follows: “Satis autem constat in Africa non ita multo post regni Vandalici finem (A.D. 354) poematiorum syllogam institutam fuisse” (ed. p. IV).

A fortunate coincidence of tradition has preserved these epigrams of Luxurius, together with the other poems of the Anthologia Latina. In an early manuscript from the 8th century, quite soon after the constitution of the antique edition (middle of the 6th century), the Codex Salmasianus (Paris. Lat. 10318) was conceived, the main witness for Luxurius: barely 200 years after the antique original.

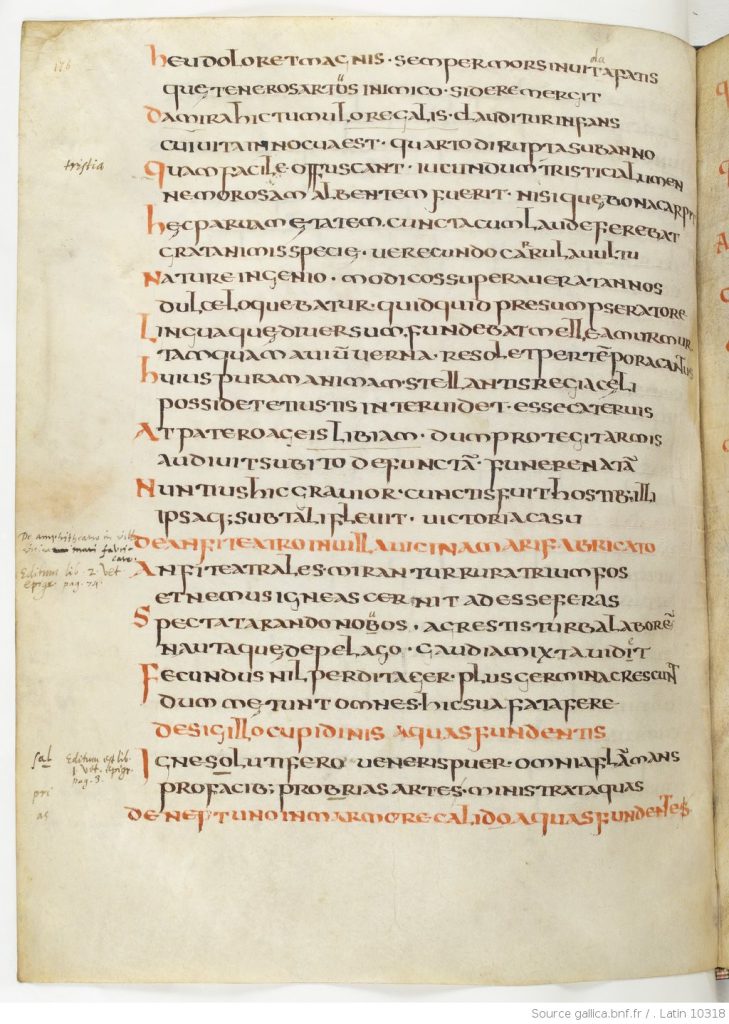

Damira’s epitaph (AL 345 R.) is of particular interest with regard to the genre question and the relationship of the poem to epigraphy: The ‘presence’ of the poet at the tomb brings into focus the question of the epigraphic character of the epigram, as it is readily assumed in scholarship that many of his poems were indeed carved in stone. After a general complaint about fate (v. 1-2) the poem turns to the person Damira – and this in typical epigraphic diction – with the deictic hic as well as the the naming and the age of the dead, both necessary elements of a grave inscription: Damira hic tumulo regalis clauditur infans | cui vita innocua est quarto dirupta sub anno (v. 3-4). A very general, almost inappropriate thematization of mors immatura interrupts the individual lament for the dead; and only then follows a renewed turn to the deceased, which makes a haec (v. 7) necessary.

For a real grave inscription of a royal person in Vandalic times we would expect more: a (prose) prescript that at least mentions the name of the person concerned in relation to her father Oageis/Euagees – a famous army commander and “Wandalenprinz” (Happ II 341), who can be determined from the later narrative addition (v. 15-18). But certainly his name would not appear on the inscription in the banal form of pater Oageis (v. 15). In addition to the indication of age, we would also expect the depositio, which is regularly noted in this period. And one misses a clear Christian commitment:

Damira’s pure soul has found home after her early death in the kingdom of the starry heaven: puram animam stellantis regia caeli | possidet (v. 13f.) – however, this hexameter closure is not a general poetic formula, but a direct borrowing from Vergil (Verg. Aen. 7, 210: nunc solio stellantis regia caeli / accipit) and thus to be explained by literary imitation. If we want to reconstruct a Christian background from this choice of words or even see a “sentiment tout chrétien” (P. Monceaux 277), this could only be obtained in distinction to Vergil. But the verse remains committed to pagan ideas – the dualism of body and soul post mortem is quite familiar to antiquity long before Christianity. And this is fully in line with Luxurius’s overall attitude in his epigrams – his world is that of Graeco-Roman mythology.

The poem at hand could at best have been an inscription, which later has been adapted in form for the literary collection. Both the general complaint (v. 1-2; 5-6) and the narrative addition post depositionem at the end (v. 15-18) indicate this. For one thing is clear: despite the deictic hic tumulo … tegitur (v. 3), the sepulchral poem is not an epigraphic text, as little as Martial’s Liber spectaculorum with its hic ubi… (II 1.5.7: hic ubi miramur) was carved in stone.

And this is the decisive point: the liber epigrammaton of Luxurius is a literary collection of epigrams written for various occasions (AL 287 R., v. 6: ex variis locis deductos). Those who believe they can prove single poems of this self-contained corpus to be epigraphic ignore the fact that clearly recognizable characteristics of the literary version oppose this. For example, in the second epitaph for a certain Olympius (AL 354 R.) neither the age nor the name of the deceased is mentioned; only a reference in the title to the preceding epigram individualizes this epitaphion supra scripti Olympii . By declaring the poems as epigraphic texts one misses the chance to track down the possible adaptation of inscriptions to literary form; that is, one misses the opportunity to get to know the poet’s technique.

More frequently than sepulchral epigrams, – only these two of Luxurius are handed down – are the descriptions of works of art, fountains, amphitheatres, gardens or other locations, – objects that are particularly suitable for linking with the text of an inscription. In general, P. Monceaux takes it for granted that all ecphrastic poems by Luxurius, which the codex Salmasianus has to offer, were really epigraphically executed and, in his opinion, must have been located above the entrance to the object described in each case.

This also happened in the case of an amphitheatre built on a country estate near the sea (de amphitheatro in villa vicina mari fabricato): Of course, this is not the grand amphitheatre of Carthage from the early imperial era; rather, a natural terrain on a rural estate – maybe framed by a wooden construction – that once offered space for animal hunting; thus no raging mass as in the Roman amphitheatre of a Calpurnius Siculus, but the country itself and the countrymen are the witnesses of the spectacula (mirantur rura – nemus cernit – spectat agrestis turba – nautaque de pelago … videt): a private complex with random spectators. The arena does not even seem to have been a sanded place, for the soil on which the ‘animals fear their fate’ is described as more fertile than ever (v. 5 f.).

Such an ‘inscription’, that doesn’t even mention the owner of the amphitheatre, that doesn’t praise the complex either, but rather describes an almost bucolic scene with random spectators, is only conceivable as a literary game. It thus completely fulfills its purpose in the liber epigrammaton – the literary collection of Luxurius.

Short Bibliography:

Clover, F. M., The Symbiosis of Romans and Vandals in Africa, in: Das Reich und die Barbaren, ed. E. K. Chryss – A. Schwarcz, Wien – Köln 1989, 57-73.

Happ, H., Luxurius I. Text und Untersuchungen, II. Kommentar, Stuttgart 1986.

Monceaux, P., Enquète sur l’épigraphie chrétienne d’Afrique. Inscriptions métriques, RA 7, 1906, 177-192. 260-279. 461-475; RA 8, 1906, 126-142. 297-310.

Schröder, B.-J., Titel und Text. Zur Entwicklung lateinischer Gedichtüber-schriften, Berlin – New York 1999, 212-219. 293-296.

Shackleton-Bailey, D. R., Anthologia Latina I. 1, Libri Salmasiani aliorumque carmina, Stuttgart 1982.

Wolff, É., Deux épitaphes de Luxorius (Anth. Lat. 345 et 354 R = 340 et 349 ShB), no. 49 et 50, in: Vie, mort et poésie dans l’Afrique romain d’après un choix de Carmina Latina Epigraphica, ed. Chr. Hamdoune, Bruxelles 2011, 299-305.

I have chosen these two epigrams, firstly for reasons of convenience: in the manuscript they appear immediately behind each other, so they can be seen on one page of the codex Salmasianus (but without the title of the first epigram, which appears on the previous page). On the other hand, they represent two different genera of epideictic epigrams, which are also represented in inscriptions: that of an ecphrasis (of an amphitheatre) and that of an epitaphion (of the child Damira). – For the manuscript variants and scholarly conjectures see Happ’s edition, for an interpretation of both epigrams, see my blog ‘Luxurius and the Epigraphic Tradition’.

Anth. Lat. 345 R. Epitaphion de filia Oageis infantula

Heu dolor! Est magnis semper mors invida fatis, | quae teneros artus inimico sidere mergit. | Damira hic tumulo regalis clauditur infans, | cui vita innocua est quarto dirupta sub anno. |5 quam facile offuscant iucundum tristia lumen! | nemo rosam albentem, fuerit nisi quae bona, carpit! | haec parvam aetatem cuncta cum laude ferebat, | grata nimis specie, verecunda garrula vultu. | naturae ingenio modicos superaverat annos, |10 dulce loquebatur, quidquid praesumpserat ore | linguaque diversum fundebat mellea murmur, | tamquam avium verna resonat per tempora cantus. | huius puram animam stellantis regia caeli | possidet et iustis inter videt esse catervis. |15 at pater Oageis Libyam dum protegit armis, | audivit subito defunctam funere natam. | nuntius hic gravior cunctis fuit hostibus illi | ipsaque sub tali flevit Victoria casu.

Translation:

Oh, what pain! Death is always the envy of those to whom great things are predestined, it plunges tender limbs into an evil fate. Damira, a child of royal blood, has been enclosed in this tomb; her innocent life ended in the fourth year. (5) How easily sorrow darkens a cheerful light! One picks a pale rose only when it was once noble! She has filled her short life full of praise: of an extremely sweet shape, a chatterbox with a shy look, she was of a natural gift that exceeded her modest age. (10) She spoke sweetly, whatever her mouth had picked up before, her honey-sweet voice poured out in emanating murmur, like the singing of birds in spring. Now the starry kingdom of heaven has her pure soul and sees her in the crowd of the righteous. (15) But when her father Oageis, who defended Africa with force of arms, learned that his daughter had suddenly died, this news burdened him much more severely than all his enemies; even Victoria wept over this stroke of fate.

Anth. Lat. 346 R. De amphitheatro in villa vicina mari fabricato

Amphitheatrales mirantur rura triumphos | et nemus ignotas cernit adesse feras. | spectat arando novos agrestis turba labores | nautaque de pelago gaudia mixta videt. |5 fecundus nil perdit ager, plus germina crescunt, | dum metuunt omnes hic sua fata ferae.

Translation:

The land marvels at victories in the amphitheater and the grove notices unknown animals here; the peasants whilst ploughing look at hitherto unseen endeavors and the sailor sees a variety of pleasures from the sea. (5) The soil has not lost its fertility, more seeds grow, while all wild animals fear their fate here.

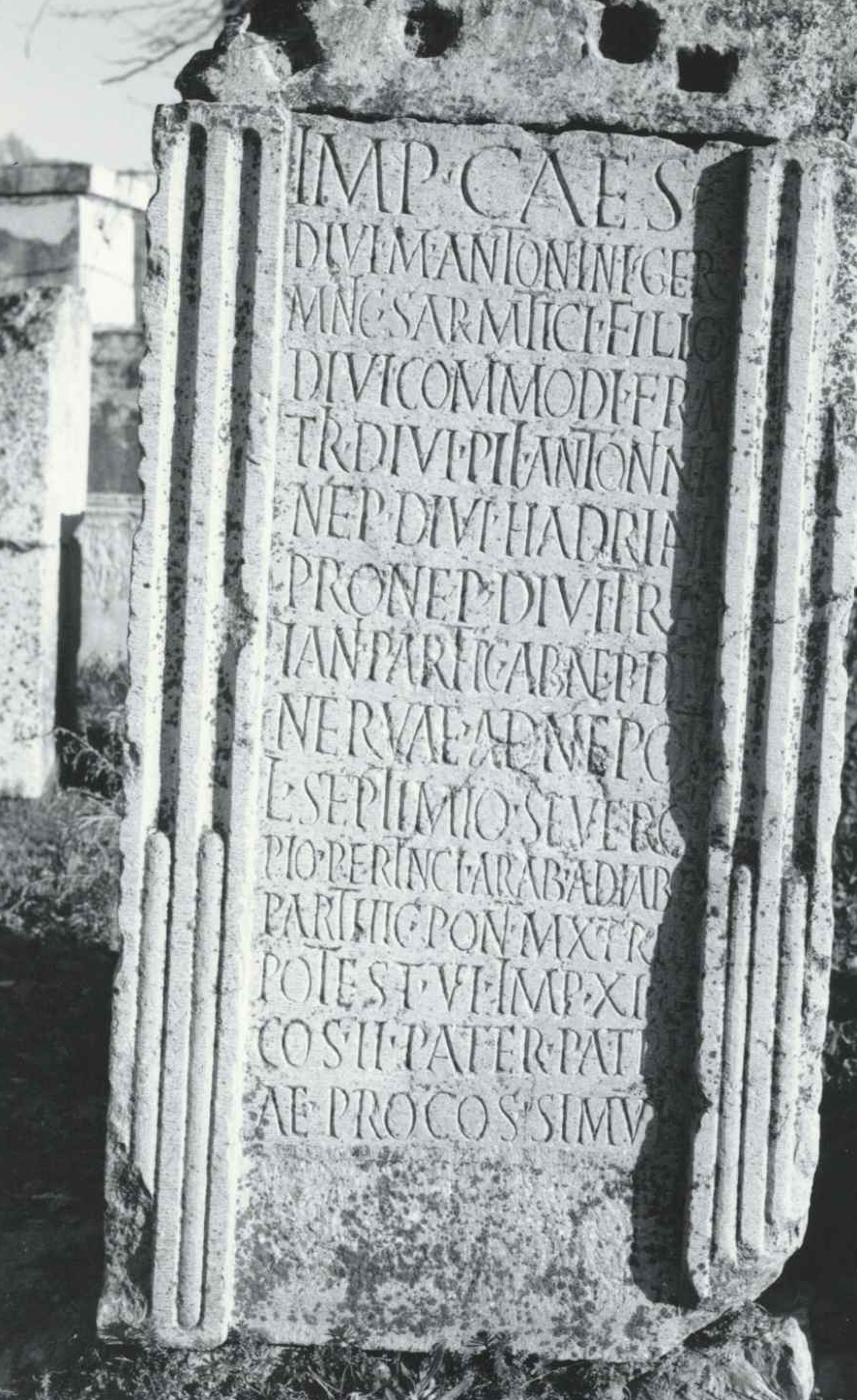

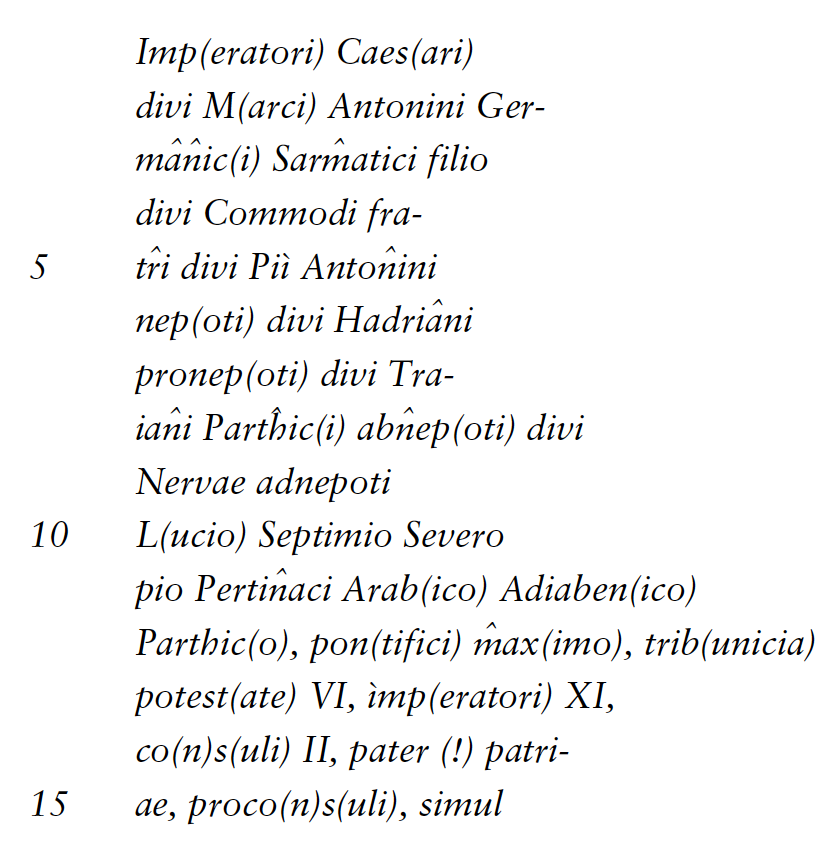

In this day and age, ancient inscriptions are seldom preserved in their original context. Moreover, the monument itself might be damaged or incomplete, so that an object that was on display outside the Museum of Lambaesis without any indication of its origin must first find its archaeological and historical context (photos by H.-G. Kolbe in 1966).

Ideally, the text and the execution of the monument provide us with suitable clues for a contextualization; and a comparison with the local epigraphy of the same time horizon may even permit a historical classification – especially when it is an imperial inscription, as in this case.

The hitherto unpublished inscription, which is presented here, seems to be without any loss of text; framed by fluted pilasters, the inscription field is completely preserved. The monument, however, lacks a crowning at the top and a base at the bottom as well as the statue, that once was placed on it. The inscription is executed in well-proportioned, elongated letters, the decorative ligatures, excess lengths of the letters T and I longae as well as comma-shaped punctuation underline the elegant character of the lettering, which is oriented towards the scriptura actuaria. The first line in larger letters catches the eye with the beginning of the emperor’s name, and so does the 10th line with its continuation after the long fictitious line of ancestors (v. 2-9), as it is quite common for inscriptions of the Emperor Severus.

To the Emperor Lucius Septimius Severus Pertinax (with the victorious surnames) Arabicus, Adiabenicus, Parthicus, son of the deified Marcus Antoninus Germanicus Sarmaticus, brother of the deified Commodus, grandson of the deified Pius Antoninus, great-grandson of the deified Hadrian, great-great grandson of the deified Traianus Parthicus, great-great-great grandson of the deified Nerva, the greatest priest, in possession of the tribunal power for the sixth time, for the eleventh time proclaimed emperor, consul for the second time, father of the fatherland, proconsul; at the same time…

An almost identical dedication to the imperial family from exactly the same time and location (CIL VIII 2550 = 18045) makes us think also in this case of a multi-part presentation and hence of a more extensive text. For in the inscription, we do not only miss the sons of Severus and Iulia Domna, but also a high-ranking dedicant figure such as Q. Anicius Faustus, the governor of the province of Numidia in AD 197/198, who is known from many inscriptions of Severian times in Lambaesis: “In African epigraphy, Quintus Anicius Faustus has only emperors and gods as rivals in frequency of attestation” (P. I. Wilkins).

However, there is nothing spectacular in this dedication to Severus: the fictitious line of ancestors back to Nerva is well known from other inscriptions of this emperor, and also the elements of his titulature are confirmed by coins and other inscriptions: They lead to a dating at the end of AD 197 or most likely to the beginning of 198, since Severus took over the tribunicia potestas for the sixth time on 10 December AD 197, but in this inscription he is not yet called Parthicus maximus – a title which he held after the celebration of the Victoria Parthica in Rome on 28 January AD 198.

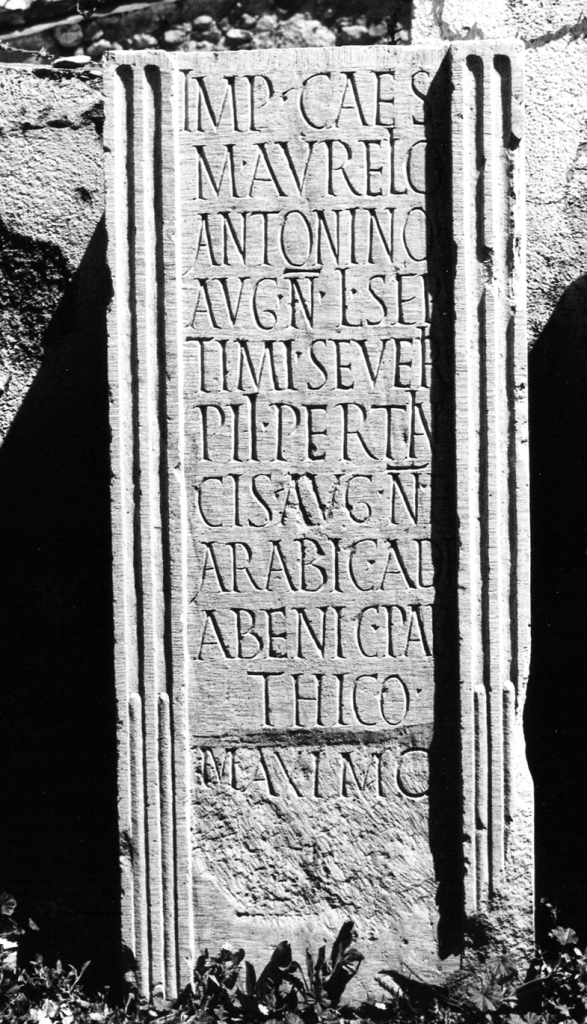

This honorary monument was thus set up at a time when Severus was still in Syria; and certainly the Emperor’s victory over the Parthians was the reason for this honour, though: anticipating the celebration of Victoria Parthica, it was set up in January and probably encompassed the imperial family as a whole. It is thus one of many honours that the Severian family received from the military stationed in Lambaesis during this time. Surprising because singular – and treacherous – is the word SIMVL at the end of the inscription, connecting two parts of one text and thus demanding a continuation of the inscription, that is: with the emperor himself, both his sons and Iulia Domna must have been honoured “at the same time”. We can recognize the continuation of this text in an inscription for Caracalla, which also comes from the military camp in Lambaesis and which shows the same fluted pilasters as its framing. This unpublished inscription reads as follows:

To the emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, our Augustus, son of Lucius Septimius Severus Pius Pertinax, our Augustus, (with surnames) Arabicus, Adianbenius, Parthicus <maximus> …

M. Aurelius Antoninus, that is Caracalla, appears in this inscription as Parthicus maximus – however, one can clearly see that maximus was added later in clumsy writing on the erased field as the last word – an addition pointing to the time after the death of Severus (Feb. 4 in AD 211), when Caracalla officially bore this title. There is no reason why the inscription for Caracalla should not be seen as part of an ensemble erected in January AD 198 in honour of the imperial family and in recognition of the conquest of Ktesiphon. It is thus a further testimony to the many honours bestowed upon the Severian House in Lambaesis after the Parthian War.

Bibl.: On the fall of Ktesiphon and the Second Parthian War see Z. Rubin, Chiron 5, 1975, 419-441.

It has always been an archaeologist’s dream to discover cities or monuments that have disappeared and whose existence we know only through literary, numismatic or epigraphic evidence.

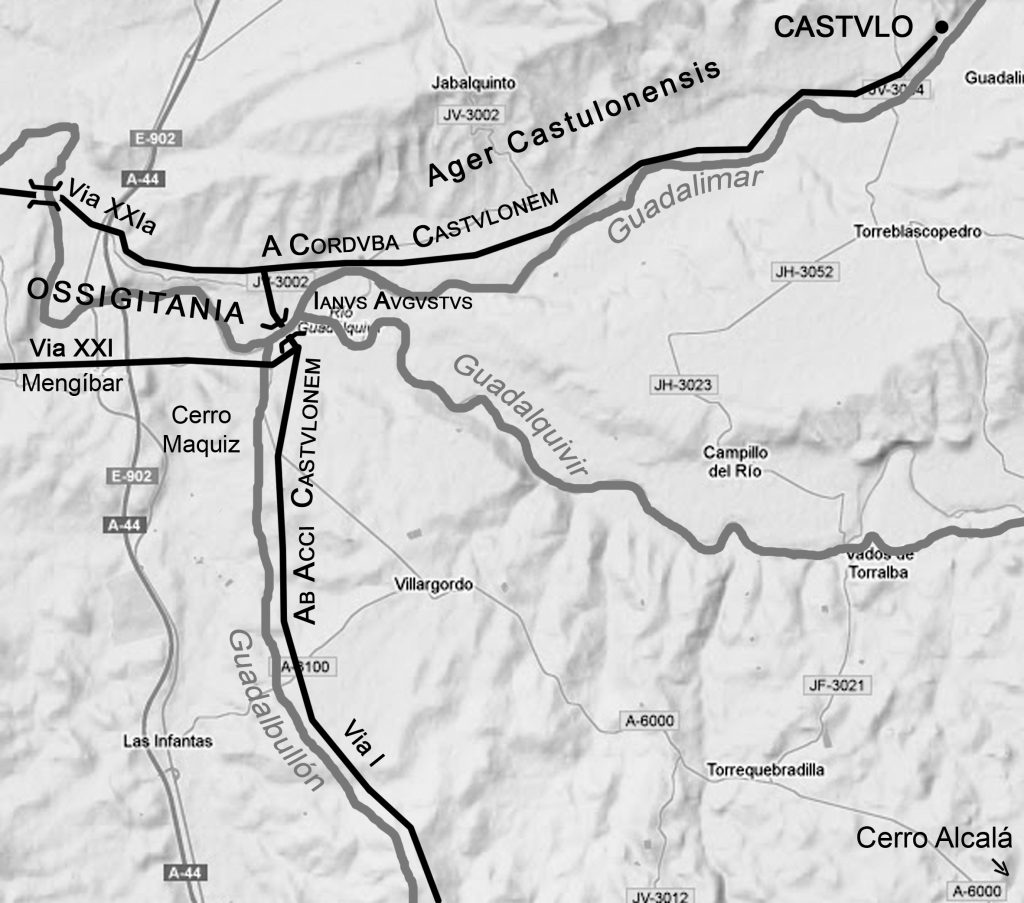

One of these monuments is the so-called Janus Augustus, known only from inscriptions. Until recently, efforts have been made to localize it; and an archaeological team from the University of Jaén now believes to have found the foundations of this Janus a few miles north of Mengíbar. I will abstain from commenting on this and would prefer to listen to the sources that give us a fairly accurate picture of the border zone between the provinces of Baeticaand Tarraconensis, in which the Janus Augustus once stood.

Further reading on recent research of archaeologists from the Univ. of Jaén:

https://elpais.com/cultura/2018/05/23/actualidad/1527075997_311298.html

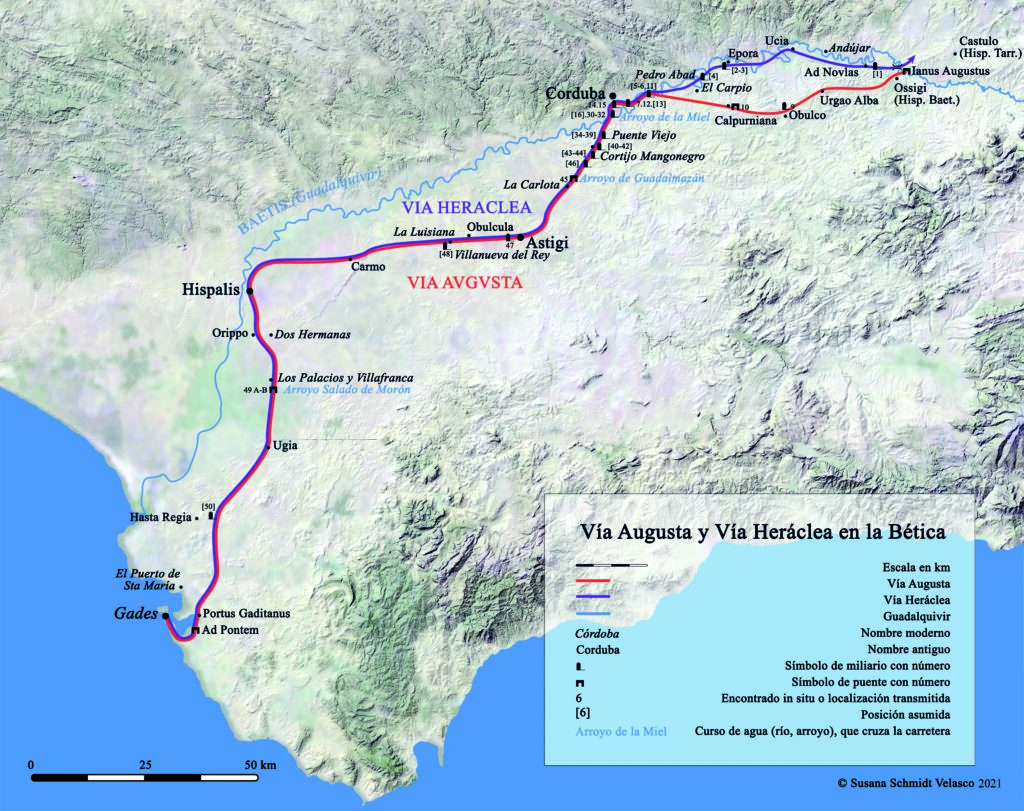

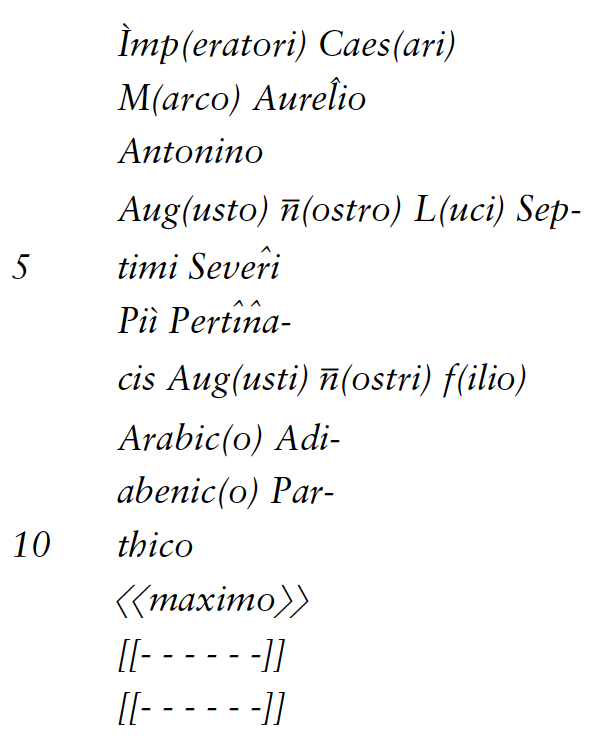

According to the milestones from the province of Baetica in southern Spain, that impressive monument stood at the gateway to this province, by the river Baetis (Guadalquivir), which also gave the province its name. It is the starting point of the via Augusta , which led from this Janus across the province to Gades (Cádiz) at the Atlantic Ocean: a Baete et Iano Augusto ad Oceanum – “from the Baetis and the Janus Augustus to the Ocean” (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum II 4709-4712; 4715) – the milestones indicating the distances from this starting point, the caput viae Augustae. Another milestone specifies this point as the entrance to the province of Baetica: ab arcu, unde incipit Baetica – “from the arch where the Baetica begins” (CIL II 4721).

The Janus or arch, probably a quadrifrons just like the Janus in Rome and comparable in shape to the Roman arch of Cáparra (Extremadura, Spain), was located at the river itself, at the beginning of the Via Augusta and at the entrance to the province. Pliny the Elder does not mention this arch, but in his geography of Hispania he does refer to the point at which the river Baetis enters the province of Baetica – i.e. he indicates exactly the point at which the Janus stood:

(Baetis flumen) modicus primo, sed multorum fluminum capax, quibus ipse famam aquasque aufert. Baeticae primum ab Ossigitania infusus, amoeno blandus alveo, crebris dextra laevaque accolitur oppidis.

“At first (the Baetis) is rather modest, but ready to take in many rivers, from which the river itself abducts name and water. And as soon as it has entered the Baeticafrom the Ossigiarea, it appears friendly through its lovely river bed and is bordered on the right and left by numerous cities.“

Pliny, Naturalis historia 3, 9.

At the borderline, right at the narrows between the hills of Mengíbar and Jabalquinto (see the map), the Baetis, previously amplified by the influx of the rivers Guadalimar and Guadalbullón, gushes forth into the province of Baetica (infusus according to Pliny), and then in a lovely course flows through this province – Pliny says it in almost poetic words: amoeno blandus alveo. From here on, the river Baetis is skirted by numerous cities left and right, crebris dextra laevaque accolitur oppidis, which Pliny later calls by name: Ossigi, Iliturgi, Ipra, Isturgi, Ucia and so on (Pliny, Naturalis historia 3,10) – these are the first cities of the province of Baetica.

There is only one topographically significant point in the area of Mengíbar which is suitable for an outstanding Augustan monument like this: The Janus Augustus must have been located at the confluence of the Guadalbullón, the border river between the provinces, and the Baetis, exactly where two Augustan roads once met. It is thus fulfilling the actual purpose of such a Quadrifrons, which marks the intersection of two streets: the road of the province of Tarraconensis, leading from Cartagena (Carthago Nova) at the Mediterranean Sea to the prosperous mining town of Castulo on the one side, and the Via Augusta of the Baetica leading to the West.

An Arabic source from the 10th century mentions the remnants of a large building called Al-Haniya – “the arch” precisely at the river Guadalbullón (Arab. wadi Bulyun) on the road to Castulo (Arab. Qastuluna). It is commonly seen as a Roman building that once stood here. Another proof for the location of the Janus Augustus.

Bibl.: M. G. Schmidt, Ab Iano Augusto ad Oceanum. Methodologische Überlegungen zur Erforschung der viae publicae in der Baetica, in: I. Czeguhn al. (ed.), Wasser – Wege – Wissen auf der iberischen Halbinsel, Berliner Schriften zur Rechtsgeschichte 9, Baden-Baden 2018, 35-53.

Roman North Africa, especially the provinces of Mauretania Caesariensis and Numidia, i.e. the territory of today’s Algeria, is particularly blessed with Latin inscriptions that are written in verses.

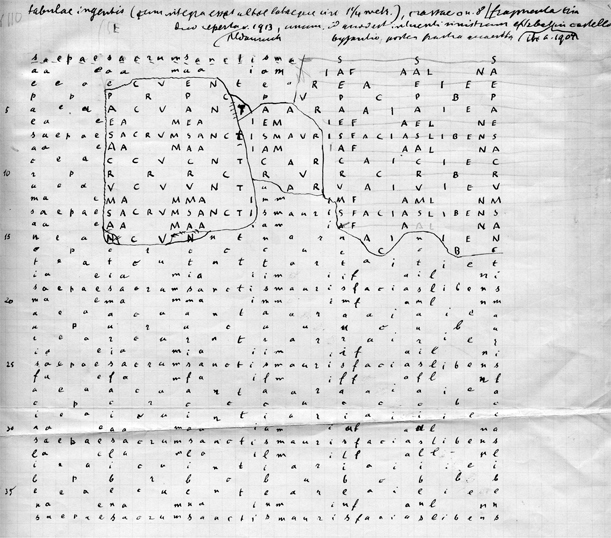

A surprisingly artistic grid inscription has only recently been recognized as such a verse inscription. It is to be regretted that apart from the epigraphic records of some leading scholars of the 19th century, the original has not survived. Nor do I know of any photo of this extraordinary inscription, so that we have to be content with the drawing by Hermann Dessau, the famous Berlin epigrapher, whose notes on Roman inscriptions are still preserved in the archives of the ‘Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum’ in Berlin.

In Madauros, the African city that became famous for Apuleius, the writer of the ‘Golden Ass’, the French scholar Stéphane Gsell luckily had reported the fragments of an enormous square plaque, the original full measurements of which must have been around 1.30m by 1.30m. «Notre table, probablement placée sur le forum de Madauros, était un avertissement donné aux dévots sous une forme ingenieuse».

The inscription was adressed to the worshippers of the African deities, the dii Mauri. But how was this ‘avertissement’, this admonition designed? In a really sophisticated and elaborate way:

SAEPAE SACRVM SANCTIS MAVRIS FACIAS LIBENS

This phrase is repeated in horizontal, vertical and diagonal script on a chess-board-like grid which originally made up 36 squares (each with sides of 3.5 cm). Gsell first considered this a tabula lusoria, but later corrected this view in his edition, in which he raised the point that the many small squares were scarcely suitable for a game. He rightly restored the whole piece on the basis of the likelihood that the first and last horizontal lines will have repeated the entire phrase: «il est probable que la 1ère ligne horizontale (comme la dernière) repétait toute la formule». And this is how Dessau reconstructed the inscription in his drawing. The grid itself was thus composed of 1,369 (= 37 by 37) small squares, each of which held one letter:

But neither Gsell nor Dessau could provide an adequate explanation of this inscription, its unusual spelling or its composition. I see it as a magic square of letters, which presents a sophisticated play on the number six: the six words Saepae sacrum sanctis Mauris facias libens appear written variously in horizontal, vertical and diagonal script. Three of these words begin with S, three end with this letter. These words, in turn, each contain six letters: sacrum, Mauris, facias, libensand also saepae. Only the form sanctis, with seven letters, does not conform to this pattern, as it not only begins with S, but also ends with a seventh letter, S – intentionally. For, to present six times six interlinked squares, not six but seven horizontal and vertical lines are required to form the sides of the squares. Therefore, the acrostic formula on, for example, the left-hand-side requires not 36 but 37 letters to provide the same reading on the lowest, horizontal line of letters.

Further – something which has not been noticed either – the phrase presented in these variations forms an iambic senarius – i.e. a play on the number six in poetic form, too. Thus the spelling saepae reflects not only a wish for a word with six letters, but also an attempt to insist on a longum in the second syllable of the first iambus by spelling saepeas saepae:

Saepáe sacrúm sanctís Maurís faciás libéns.

“Sacrifice frequently and gladly to the Moorish Gods”.

To sum this up: in six times six squares, an iambic senarius is repeated vertically, horizontally and diagonally, the senarius made up of six feet and six words each with six letters (all except sanctis).

For further reading see: M G. Schmidt, Inscriptions from Madauros (CIL VIII 28086-28150), in: A. Mastino al. (ed.), L’Africa Romana XVII: Le ricchezze dell’Africa. Risorse, produzioni, scambi (Sevilla 14-17 dicembre 2006), Roma 2008, esp. 1916–1919.

A second look at an inscription is often worthwhile, even if this seems so trivial at first. A sepulchral inscription from Timgad certainly deserves such attention: some time ago I had presented this text in a Festschrift, and after a fresh review new aspects have arisen.

This small, neatly smoothened marble panel with elegant and artfully interlaced letters (so-called ligatures) can be recognized as a titulus strictly spoken, a ‘label’, only by the volute-like ansae or double loops on both sides: they were used to attach this panel to a larger monument, – possibly underneath a niche containing a bust or the urn of the deceased.

The text reads as follows:

Aeternae securitati | M(arci) Licini Felicis qui et Ballan|tis fl(aminis) p(er)p(etui) qui vix(it) a(nnos) ter tricen|os ternos conviva divi|tum hic sepult(us) est.

To the eternal security of Marcus Licinius Felix, who is also called Ballans, flamen (priest) for life, who lived three times thirty-three years, table companion of the rich; he is buried here.

In the first three lines, abbreviations in the nomenclature such as fl. p.p. for fl(amen) p(er)p(etuus) as well as a multitude of ligatures complicate the immediate understanding of the text: Marcus Linicius Felix, with the agnomen Ballans, was a member of Timgad’s upper class – as flamen perpetuus he stood in social rank directly under the duoviri, the two mayors, and above the other priests and magistrates of the city. The ‘Album of Timgad’ (4th century AD), an inscribed list of municipal officers and priests, gives us information about the composition of the flamines perpetui and their social standing. The question whether the very elderly Felix could still perform the function of a flamen perpetuus, we will leave for now.

The last two lines manage with far fewer ligatures and abbreviations and are accessible to the reader at first glance. The reason for this may have been that the dedicator of the inscription did not want to obscure the poetic character of this particular section. Anyone who reads these lines aloud will recognize a trochaic septenar in the final part of the text that holds a surprise in store.

Qui vixit annos ter

trícenós ternós convíva | dívit(um)_híc sepúltus ést

tells of a 99 years old man who was a “table companion of the rich” (conviva divitum). We notice that no relative is named as the person responsible for the funeral. Since the term conviva divitum appears in the sepulchral context (hic sepultus est), the community of divites might have played a special role in the fulfillment of the last duty towards their table mate, for the purpose of such social clubs was not only to hold regular celebrations and business meetings.

Anyway, in this inscription, for the first time a convivium divitum – casually spoken: a “millionaires’ club” – is mentioned. “Rich” is a term that is not explicitly mentioned otherwise in the assignment of Roman social ranking, but which reflects a tangible reality, as the municipal magistrates had to meet a certain minimum census. Obviously the elite of Timgad was not only strongly oriented toward offices and priestly dignities in their prestige striving, but had also found an appropriate social network in such a “club of the rich”, which probably also took over responsibility towards its members.

Bibl.: M.G. Schmidt, Ein convivium divitum in Thamugadi, in: B.-J. and J.-P. Schröder (ed.), Studium declamatorium. Untersuchungen zu Schulübungen und Prunkreden von der Antike bis zur Neuzeit (Festschrift Joachim Dingel), München – Leipzig 2003, 395-400; here further literature on individual aspects, e.g. H. Pavis d’Escurac, Flaminat et societé dans la colonie de Timgad, Antiquités africaines 15, 1980, 183 sq.; for the text see O. Salomies, in: Année épigraphique 2003, 2018.

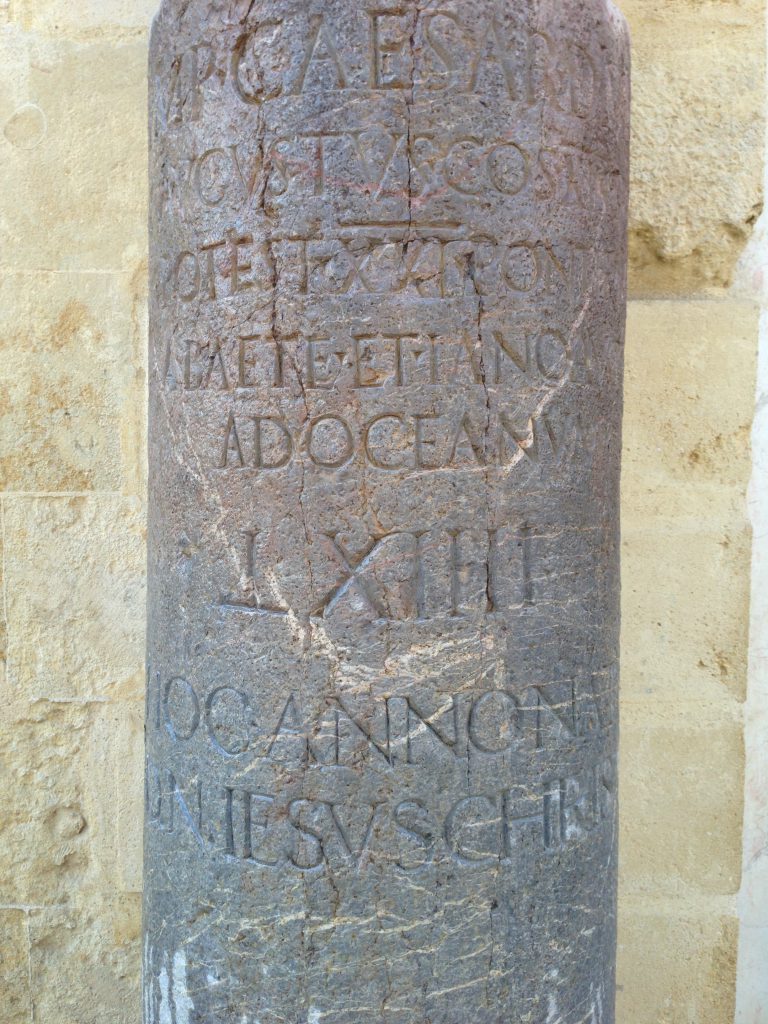

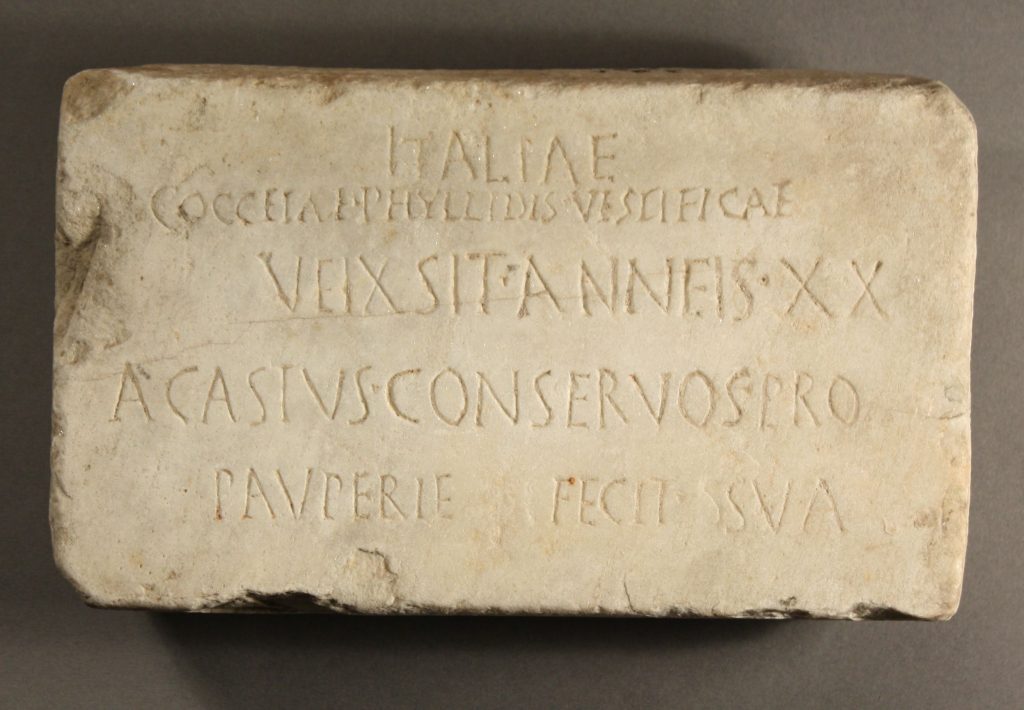

The recently published catalogue of the ‘Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden’ shows the gravestone of a Roman slave whose inscription has been known for some time:

Italiae | Cocceiae Phyllidis vestificae | veixsit anneis XX | Acastus conservos pro | pauperie fecit sua (scil. manu).

„For Italia, seamstress of Cocceia Phyllis. She lived for 20 years. Acastus, her fellow slave, made (this inscription) out of destitution by his own hand.“

However, the reference to the execution of the work (fecit sua manu), which can now be checked on the photo, has remained unnoticed till now – not a stonemason had engraved Italia’s inscription, but Acastus, a slave from their common household, who apparently was close to the deceased.

To the best of his ability and by his own hand, the slave had clearly tried to place the inscription on the centre of the stone in beautiful, even letters, so that Italia would receive an appropriate memory.

But he made a decisive mistake – not in spelling or grammar (although the Latin seems a little bit old-fashioned, e.g. the spelling EI for long I): Acastus had forgotten to indicate the name of their mistress, the patrona. Apparently by second hand, which shows a more fluid ductus of smaller letters in the so-called Scriptura actuaria, a line was inserted in which her name is now mentioned – Italia was the seamstress of Cocceia Phyllis: of course, a slave’s grave inscription required the patron’s consent!

After Acastus had made every effort to create a well-balanced layout, now there was this disturbing addendum, after the inscription had already been completed! Thus, Phyllis did herself a disservice, which will remain carved in stone forever.

Bibl.: Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden – Skulpturensammlung. Katalog der antiken Bildwerke IV. Römische Reliefs, Geräte und Inschriften, ed. K. Knoll – Chr. Vorster, München 2018, 285 no. 104.